“This is my body which is given for you: this do in remembrance of me.” Luke xx.xviiii

+In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost. Amen.

I TAKE MY TEXT this morning, not from the readings, but from a very familiar verse. There is much to be gained and much to be learned from this morning’s readings, though, so please don’t miss them. I commend them for your inward digestions through the week. Yet, as we all know: familiar hymns, bits of the liturgy and scripture are like old friends—the best kind of old friends, the ones you can not speak to for years, then pick up together and carry on like you saw each other last week. We know that if we can but hear these old friends, these little bits of life-giving words, we can awaken in ourselves a deeper revelation of God’s love. How many times have we found ourselves in trouble only to hear, “Peace, be still” or “The Lord is my Shepherd, I shall not want,” or “There is a balm in Gilead,” and upon remembrance of these things, suddenly find ourselves in calmer waters, greener pastures–knowingly safe in the hands of Him who made us?

So, today, if you’ll permit me, I’d like to sit together with a verse said at every Mass. You’ll hear it again here in a few minutes accompanied by ringing bells. We might breeze past it without a thought as we bow our head and cross ourselves. We might miss it when greeting its recitation with genuflections. This verse, itself, is the very command our Lord gives us in St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians. What’s been given to me, St Paul writes, I now give to you: on the night Our Lord was handed over to suffering, he took the bread, gave thanks and broke it, and said, HOC EST ENIM CORPUS MEUM or “This is my body.”

YOU MIGHT SAY it starts with rain. But it’s hard to say exactly where it begins. It could start with the sun, the seed, or the fecund earth—but for this morning, for this sermon, let’s just say it starts with rain. Water from the earth evaporates, then gathers in the sky to form clouds. When clouds grow gathered heavy, it rains. This rain gives life wherever it falls, and, today, let’s say it falls on a kernel of wheat that eventually becomes Christ’s body.

The kernel of wheat was planted in well-tilled soil, in rich dark earth of fields. The farmer, herself, knew when to plant at just the right time. She knows how deep to plant the seed. She knows how to care for it. She knows how to take that seed and turn it into tall wheat by summer’s end that eventually becomes Christ’s body.

This wheat, fed by sunshine and rain, by delicate care is then sent to the threshing floor where the chaff is winnowed away. The remaining kernels, the good kernels, are ground into flour. This is the flour that eventually becomes Christ’s body.

Then, according to the Passover tradition, this flour is mixed with water and baked to make unleavened bread. It is this bread that a priest handles in persona Christi to make into Christ’s body.

You know all this, of course, don’t you? You passed Elementary science. In fact, I can imagine many of you in the pew have a better grasp of this than me, a lowly writer with no science mind. But, I bring this up to ask a question, perhaps it’s one you’ve never considered: when Christ held up the bread and said “This is my Body,” what was he referring to? When he held up the bread, did he not also hold up the cook, the flour, the kernel and the chaff, the earth, the farmer, the fecund earth, the rain, the clouds–the whole great chain of being all the way from the Big Bang to his Second Coming, straight through me and you, right there in the pew?

This is the problem with the word made flesh, with the VERBUM CARO FACTUM EST, with the divine invasion into his creation: where does the divinity start and where does humanity end?

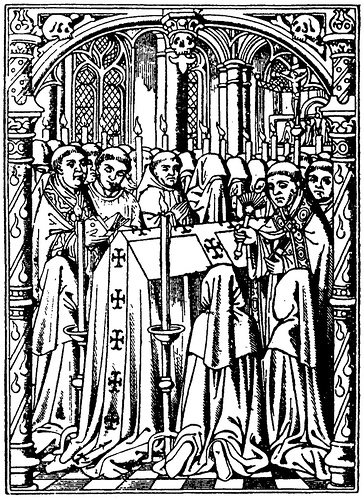

Can we find all the world in a loaf of unleavened bread? Can the totality of creation fit in the chalice? Oh, how the altar should buckle under this weight! A priest should tremble with this burden in his hands! How our choirs should shout to be heard over the teeming tumult of the living and the dead in the bread! How we should see ourselves there in a priest’s hands! It is indeed, unto all creation gathered up in that bread that Christ whispered at that first Mass, HOC EST ENIM CORPUS MEUM. All of this is his body.

NOW, YES, YOU know that it takes faith to see this, to see the world as the body of Christ, but please know it does not take belief for it to be. Let me say that again. I don’t want you to miss this: to see this rain-soaked-baked-wheat as the Body of Christ takes faith. But it does not take belief for it to be the Body of Christ.

This miracle happens–or, is happening, rather–whether you see it or not. You’re probably familiar with the saying, “bidden or unbidden, God is present.” It’s the same thing. God’s existence is not determined by your belief. You can disbelieve in God all day, all night, yet here he is, going right on existing nearly in spite of your disbelief. The GREAT I AM needs not your belief to be. Nothing hinges on your doubt; nothing is dependent upon your faith.

Yet, we do pray that we may be partakers in this mystery. We do pray to see it. And, thankfully, the Church gives us signs and symbols to help. Here in a few minutes when the words are spoken over the bread and wine, we will bow and genuflect. The sanctuary will grow dense with the fog of incense. We ring bells and raise candles as if to say: pay attention, look up, this is it! At Evensong and Benediction, we take this bread-made-body, enclose it in gold and bless the gathered. At Corpus Christi, we take the body-made-bread and go for a walk, blessing the neighborhood: the world meeting the world in Christ’s body. Pay attention, these rituals all say.

BUT IF CARE be not taken, all these signs and symbols can become a Tower of Babel. Do you remember that story from Genesis? All the men and women were all gathered in one place and spoke one language and decided together upon one most beautiful goal: they would build themselves a tower to God. But, God, frustrated at their plans, strikes them with diverse tongues. Unity dissolves and confusion reigns for none can understand the other! The great Tower, the great goal of union with God, goes unbuilt.

The goal itself, the goal of union with God, is not a bad goal. It’s surely not a sin to desire to be one with God! There is a way to be one with God, but a tower isn’t that way. One peoples, one language, one goal is not the way. And it is God himself who frustrates their plans. We must be careful in building our faith that we’re not just inadvertently building a Tower of Babel.

Beware, beloved! Theology and signs and symbols and rituals can, too, become a Tower of Babel if we’re not careful. The temptation to think if we can just get the architecture right, we might say, then the Divine will always be with us. If we can just understand correctly, have the right theology, believe the right things about the right people, then the Divine will always be with us. If we can just get everyone to sing on pitch, lustily and with good courage, then, surely, the union of God and Man is not afar off.

But, just like at the Tower of Babel, God himself will confound us when every brick of thought is laid. He will confuse us when our blueprints become too perfect. He will send delay after delay when we think our faith has become right. The moment when we think we understand God, it’ll be all confusion and doubt and pain—all wrought from His own hands. It’ll take decades to see the blessing of this. But, remember, my friends, this is the Lord’s own doing.

So, when we see the bread lifted up with smoke and lights and genuflections, we might be tempted to think this is his body only. After all, a priest with the blessing of a Bishop in the line of succession of Bishops through Scotland back to Christ has said the right words and we’ve done the right actions, so, surely, this bread is the body of Christ! After all, it’s ensconced in gold and with the best words, the best music. Surely his body has nothing to do with the unwashed, the naked, the hungry, the hateful, the deceitful, the general assholes of the world, the Trump supporter, and the Neo-Nazi, and all who have hurt us. Surely this body is better than all the bodies of this world, including my own with its bad teeth and flab. And, thus with clanging cymbals we build a Tower of Babel to God and the whole world is lost! Christ is lost!

SO, MY FRIENDS, as I said earlier, if it takes faith to see, but not faith for it to be, then how exactly are we to be partakers in this mystery if God will frustrate all our attempts at it? How can we “taste and see that the Lord is good” if words—even the best words—only get us so far? How can we eat his flesh and drink his blood before God gets in and mucks up all our thoughts?

What I’m about to tell you is a secret, a secret so scandalous you’ll laugh when I tell you. This is a secret that took me many long years of dark nights and dry days to learn. But, if you’ll listen, I shall tell you. Here’s what we do to really see the bread for what it is, to truly have that deeper revelation of God’s love. Are you ready? Are you sure?

Here’s the secret: there’s nothing to do.

Laugh if you must! Your laughter proves it is true!

Now, there is a great temptation when we hear there is nothing to do to think we must do nothing. But this is not what I’m saying. Doing nothing can become just another Tower of Babel, after all. Maybe in this Christian context of ours, what we can do is let go. Quit trying so damn hard. Maybe the best thing we can do is to rest.

When faith pierces darkness with hymns of joy and gladness: sing with your heart, then rest.

When doubt overwhelms the soul: go ahead and drown in the flood, then rest.

When belief returns like whispered dawn: welcome it with a kiss, then rest.

When it’s time to be born, just be born—then rest.

When it’s time to plant, just get farming—then rest.

When it’s time to pluck up, just get to the harvest—then rest.

When it’s time to kill, just do it with mercy—then rest.

When it’s time to heal, just bind up the wounds—then rest.

When it’s time to break down, wield a sledgehammer—then rest.

When it’s time to build, just get to work—then rest.

When you laugh, laugh every bit of all your laughter—then rest.

When you cry, leave not a tear unshed—then rest.

When you mourn, weep upon another’s shoulder—then rest.

When you dance, may your feet find abandon—then rest.

When it’s time to die, just die—then rest.

Do you wish to see the Body of Christ? Do you wish to see, perhaps, for the first time, this miracle of bread-made-flesh and of flesh-made-world? Of all creation in an unleavened loaf? All you have to do is open your eyes. Do you wish to see how Christ would act in the world? Watch your your own feet and look to your own hands. Do you want to have the mind of Christ? Look to your own mind and, yes!, there it is! It’s here for your seeing. Don’t believe—just let go and look!

SOON, AFTER THE Creed and the prayers, and the confession and offertory, when the sanctuary is once again thick with the prayers of the faithful throughout all ages past and future, and when angels peer from behind pillars to cry continually to the other, Hosanna, Hosanna in the highest! And the lion lay with the lamb by the crystal sea, smooth like glass, before the throne, the words will be spoken, “This is my body, broken for you,” and bells will ring and we will look up. Come out of your tower to worship him. Don’t miss it! Don’t let him pass by!

This is it, friends! This is it! This is it!

(On left, the author in 2014. On right, in 2016, after a year of dieting, cardio and strength training)

(On left, the author in 2014. On right, in 2016, after a year of dieting, cardio and strength training) Here, now, at this spot—and not another—I would introduce Zazen or koans, those medicines that bring me back to earth with perhaps a high sentence or three and rhetorical flourish. I would introduce calorie-counting or exercise here, too, including six easy steps to rid belly fat and you won’t believe his reaction (and doctors hate him, of course) and the like. But as wonderful as these are, they were not my salvation.

Here, now, at this spot—and not another—I would introduce Zazen or koans, those medicines that bring me back to earth with perhaps a high sentence or three and rhetorical flourish. I would introduce calorie-counting or exercise here, too, including six easy steps to rid belly fat and you won’t believe his reaction (and doctors hate him, of course) and the like. But as wonderful as these are, they were not my salvation.